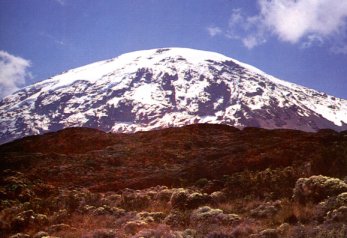

Kilimanjaro History

. There is certainly a reliable supply of water which, together with the rich volcanic soil in the area, makes the foothills

of Kilimanjaro ideal for cultivation.

Of course, the Chagga's knew this and when a group of British settlers, led by Sir Harry Johnston, the writer and

naturalist, arrived here in 1884 the also took advantage of these conditions. They cleared and planted an area of land

near Taveta, to the east of Kilimanjaro's foothills. Johnston had visions of the region becoming a 'second Ceylon'.

In 1886, when the governments of Germany and Britain agreed on a border to officially define their territories, the line

they drew – from Lake Victoria to the coast - was perfectly straight, broken only by an untidy curve around Kilimanjaro.

This divided the original British territory claimed by Johnston, now in Kenya, from the rest of the area, now in Tanzania.

You may be told that the border curves around Kilimanjaro because Queen Victoria gave the mountain to Kaiser

Wilhelm (her grandson) as a birthday present. While such an action would have been no different to the arbitrary

partitioning of East Africa by these two monarchs' own governments, there is no evidence that this story is true. But

it remains one of many popular myths that add to the mystique and attraction of Kilimanjaro.

There is certainly a reliable supply of water which, together with the rich volcanic soil in the area, makes the foothills

of Kilimanjaro ideal for cultivation.

Of course, the Chagga's knew this and when a group of British settlers, led by Sir Harry Johnston, the writer and

naturalist, arrived here in 1884 the also took advantage of these conditions. They cleared and planted an area of land

near Taveta, to the east of Kilimanjaro's foothills. Johnston had visions of the region becoming a 'second Ceylon'.

In 1886, when the governments of Germany and Britain agreed on a border to officially define their territories, the line

they drew – from Lake Victoria to the coast - was perfectly straight, broken only by an untidy curve around Kilimanjaro.

This divided the original British territory claimed by Johnston, now in Kenya, from the rest of the area, now in Tanzania.

You may be told that the border curves around Kilimanjaro because Queen Victoria gave the mountain to Kaiser

Wilhelm (her grandson) as a birthday present. While such an action would have been no different to the arbitrary

partitioning of East Africa by these two monarchs' own governments, there is no evidence that this story is true. But

it remains one of many popular myths that add to the mystique and attraction of Kilimanjaro. revered. When Johannes Rebmann reached this area in 1848, and became the first European

to see Kilimanjaro, he reported that his guide has once tried to bring down the 'silver' from

the summit, which mysteriously turned to water on the descent. A later explorer, Charles

New, who reached the foothills of Kilimanjaro in 1871, heard stories from the local chief Mandara

about spirits on the mountain jealously guarding piles of silver and precious stones.

It was said that anybody trying to reach the summit would be punished by the spirits with illness

and severe cold.

New was later followed by other explorers: Gustav Fischer and Joseph Thomson both reached the lower

slopes of Kilimanjaro, and in 1887 Count Samual Teleki managed to get to a point only 400 metres below

the top of Kibo. The summit was eventually reached in October 1889 by Hans Mayer, a German professor

of geology, accompanied by Ludwig Purtscheller, an experienced alpinist and Yohannes Lauro, a local guide

from the village of Marangu. Mayer named the summit Kaiser Wilhelm Spitze, after the German emperor.

When mainland Tanzania (then called Tanganyika) gained independence in 1961, the name of the summit was

changed to Uhuru (Freedom) Peak.The derivation of the name Kilimanjaro has never been satisfactorily explained. Rebmann believed that the name meant "Mountain of Greatness" or "Mountain of Caravans" (slaving caravans travelling between the coast and the interior would have used the mountain as a landmark). Other writers have since suggested that the name means "Shining Mountain", "White Mountain" or "Mountain of Water".